Reform to Restoration: French Art from Louis XVI to Louis XVIII from the Horvitz Collection

August 17, 2025

Reform to Restoration, an exhibition of French art from the Horvitz Collection, shows how artists from 1770–1830 responded to political and cultural upheaval through classical themes and academic tradition.

Spanning 10 years of artistic production, this exhibition highlights three extraordinarily pivotal epochs in French history: the French Revolution (1789–1799) and the creation of the French Republic; the rise of Napoleon Bonaparte and his ultimate defeat in 1815 at Waterloo; and the Restoration of the French monarchy (1814– 1830) under Louis XVIII and Charles X. This period was marked by an artistic shift from the ornate Rococo style favored in the French court to a revival of interest in the themes and aesthetics of classical antiquity known as Neoclassicism. Eventually, this led to the emergence of Romanticism, a movement emphasizing subjectivity and emotion as a response to a growing disillusionment with the Enlightenment ideals of reason and logic in the aftermath of the Revolution.[1]

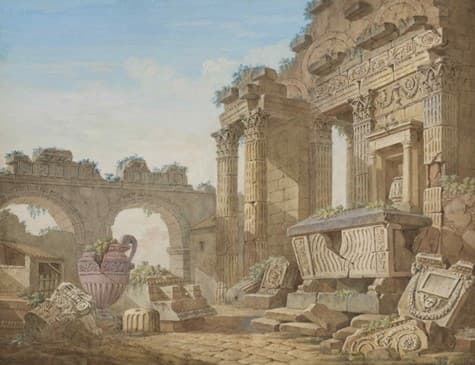

All the objects in Reform to Restoration are drawn from the Horvitz Collection, one of the most important private collections of French art in the United States. More than 100 drawings and paintings are organized around six thematic categories: Antiquity, Revolution, Devotion, Service, Empire, and Honor. Each grouping reflects the variety of social concerns, political events, and visual movements that influenced artists living in the tumultuous period between 1770 and 1830, including many well-known artists such as Jacques-Louis David and Jean-August- Dominique Ingres. The exhibition begins by exploring the French Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture, which was founded in Paris in 1648. This state-sponsored institution promoted a curriculum based on mastering the human form through the practice of drawing live models. At the same time, the Academy encouraged studying the Greek and Roman classical traditions, as seen in the work of architect and artist Charles-Louis Clérisseau, who spent roughly two decades in Rome. In his Capriccio with Ruins (1789) [fig. 1], for instance, we see an imagined landscape of ancient Roman monuments that combines real architectural elements with fantasy, a popular 18th-century genre. The enthusiasm for the classical past had significant resonance across French politics and culture, most notably in the wake of the Revolution, when the government was reconceived in the model of the ancient Roman Republic (circa 509–27 BCE). In Allegory of the Revolutionary Regime [fig. 2], artist Louis Lafitte utilizes classical sources, such as the Roman poet Horace and the ancient Roman historian Livy, to critique the Revolution, and particularly its most violent phase, the Reign of Terror. In the foreground, before the Temple to Janus (the god of transition and time), the allegorical figures of War and Conflict overcome Justice, suggesting the Revolution resulted in injustices similar to early Republican Rome.[2]

Other works in this exhibition deal with the theme of devotion, whether romantic, religious, parental, or patriotic. One example is Pauline Auzou’s enigmatic painting Daria or Maternal Fear (1810) [fig. 3]. A beautiful young mother in what appears to be a Baltic folk costume kneels before a sapling split in two. The watering can and shovel at her feet may refer to the custom of planting a tree when a child is born. The mother grips her squirming child protectively, her face slack with dread, apparently shaken by the sinister omen of the broken tree. Critics praised Auzou’s achievement when she presented Daria at the 1814 Salon, but wondered about the source material for the subject, which she never revealed.[3]

Like Pauline Auzou—who depicted Napoleon Bonaparte, Charles X, and other members of the ruling class—many artists found success serving the interests of the State. Allegory of the Concordat by Antoine-François Callet [fig. 4] is either the preparatory drawing for, or a record of, the now-damaged oil sketch submitted to an art competition in 1802. The competition celebrated both the Treaty of Amiens, which temporarily ended a war with Spain and Britain, and the signing of the Concordat of 1801, a restoration of ties between France and the Catholic Church that were severed during the Revolution. Previously the portraitist of King Louis XVI, Callet skillfully adapted to the changing political tides and here renders Napoleon Bonaparte in a fictional scene of triumph, modeled on Roman precedents. The future emperor, crowned with a laurel wreath and illuminated by heavenly rays emanating from behind the Holy Eucharist, drives a chariot toward Notre-Dame, dragging a representation of Heresy in chains.[4]

Colonial ambitions were strong under Napoleon’s rule. The French government became known as the First French Empire—a deceptive designation, given that France had maintained colonies in the Americas and Asia since the 17th century. In 1798, Napoleon’s forces invaded Egypt—albeit in the end unsuccessfully—and returned with numerous looted art objects, many of which ultimately entered the collections of the Louvre and the British Museum. Bust of a Man in a Turban (about 1800) [fig. 5] depicts a figure whose costume is inspired by what Europeans would have encountered throughout the Ottoman Empire in the early 19th century. Moreover, the unidentified sitter represents an artistic movement termed Orientalism that portrayed people of the Middle East, Asia, and North Africa in sensational and stereotyped ways, as a propagandistic tool to justify imperial ambitions. Although France lost many of its initial colonial territories by the early 1800s, they eventually gained control of large parts of Africa and Southeast Asia in the later parts of the 19th and 20th centuries.

The exhibition concludes with a selection of paintings that consider the concepts of honor and leadership in the face of crisis, themes relevant to multiple conflicts in this era. Two paintings draw from Torquato Tasso’s poem Gerusalemme liberate (The Liberation of Jerusalem), a romanticized retelling of the First Crusade (1096–1099), in which Christian armies battle to take control of Jerusalem from Muslim forces, first published in 1581. In François-André Vincent’s Rinaldo and Armida (circa 1787) [fig. 6], we see the climactic encounter between Armida, a Saracen sorceress sent to thwart the European knights, and Rinaldo, the knight she seduced. Freed from Armida’s enchantments by his comrades, Rinaldo returns to war and his duties, but still prevents the lovesick sorceress’s suicide by arrow and converts her to Christianity. The noble and brave Rinaldo, shown here as a striking youth in shining armor who regains his honor by returning to his moral cause, serves as an exemplar in uncertain and violent times.

[1] Thank you to Dana Cowen, the Sheldon Peck Curator for European and American Art before 1950, whose notes and labels from the Ackland Art Museum’s 2023 presentation of Reform to Restoration were referenced for this essay.

[2] Isabelle Mayer-Michalon, Reform to Restoration: French Drawings from Louis XVI to Louis-Philippe (1770–1830), ed. Alvin L. Clark (The Horvitz Collection, 2024), 300–301.

[3] Andrea Morgan, “Five Favorites of French Neoclassical Art” (The Art Institute of Chicago, October 29, 2024), https://www.artic.edu/articles/1146/five-favorites-of-french-neoclassical-art.

[4] Mayer-Michalon, Reform to Restoration: French Drawings from Louis XVI to Louis-Philippe (1770–1830), 218.