Children of the Revolution: Images of Children and Families from late 18th-century France

September 5, 2025

Inspired by the exhibition, "Reform to Restoration," explore how late 18th-century French art used images of children and families to reflect the nation’s political upheaval, ideals, and hopes for the future.

French art of the late 18th and early 19th centuries often wrestled with grand themes—politics, power, history, honor, and mortality—but children and their parents were also an increasingly favored subject matter in the wake of the French Revolution and the extreme violence of the period. Both the exhibition Reform to Restoration: French Art from Louis XVI to Louis XVIII from the Horvitz Collection and the Crocker’s permanent collection feature works that turn to the quotidian theme of family life and France’s youngest citizens to explore nationalistic themes.

The Virtue of Family

As art historian Isabelle Mayer-Michalon describes, a trend emerged in French art in the late 18th century of scenes “emphasizing the happiness that family love could provide.”(1) This desire for happy subjects, specifically the family, was born both out of the existential terror of the final years of the French Revolution, which saw mass arrests and executions of those accused of defying the new regime, as well as new considerations of the role of the individual found in the works of the Enlightenment.(2) For instance, in Émile, or On Education (1762), philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778) explores the moral and social foundation of the individual from birth to young adulthood, ultimately arguing that children should be allowed to develop freely without societal constraints. The treatise foregrounds the parent’s role as a guide and protector to cultivate a virtuous individual.

This very dynamic is at play in a pair of drawings in Reform to Restoration by Philibert-Louis Debucourt, Maternal Joys and Paternal Pleasures [figs. 1–2], which spotlight the happiness of familial love. Influenced by the Dutch genre painters of the 17th century, Debucourt began his career as a member of the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture, with several works exhibited at the Paris Salon in 1781 and 1783.(3) By the mid-1780s, however, he had transitioned to primarily producing colored engravings, printed works that could be reproduced multiple times. The drawing Paternal Pleasures (circa 1796), which hangs in the exhibition next to its pendant, Maternal Joys, is the design for one of these prints [fig. 3] and depicts the absolute contentment of multigenerational relationships. At the center of the composition, a cherubic infant dressed only in his or her bonnet and clout—a kind of cloth diaper—bounces joyfully on a grandfather’s shin. To the left, a younger-looking couple tenderly grasp hands, while another woman looks on affectionately from the raised porch of a dignified home. These are the child’s parents and grandmother, completing the idyllic ensemble. Their cheerful faces and playful poses convey a sense of ebullient joy, echoed by the family dog, half-perched on the father’s lap, and the tranquil cat, sleeping on a balustrade wall. This scene of an ideal family is not purely a balm against the terror of the Revolution, but also instructive as to the role of older generations in nurturing the next to secure a brighter future. Although not explicitly a political allegory, it reinforces notions of the family unit as both a guard against corruption and a source of moral guidance.

The Power of Children

In contrast to Rousseau, the newly democratic French State was interested in influencing how society acted upon children and the family. According to the French Constitution of 1795, “No one is a good citizen if he is not a good son, a good father, a good brother, a good friend, a good husband.”(4) This was a turning point in the relationship between the government and its minor citizens; the French Revolution marked the first real interest in children as a national concern. Children were to be cared for, educated, and prepared for the responsibilities of citizenry by their government.(5) Where Rousseau emphasized individual growth and autonomy, the French Republic prioritized the formation of productive citizens through standardized and uniform educational programs. The shaping of the country’s youth was explicitly understood as an essential policy of national importance.

At the same time that broader political and social movements recognized the support of children as a public concern, the Revolution also sparked fears regarding the power of children. A pamphlet published in Paris in 1789, for example, warned of child gangs, spurred by patriotic fervor. The Revolution was a moment when many groups long suppressed by the hierarchical ancien régime suddenly had access to power, including young people. The pamphlet further warned parents, particularly mothers, to steer their children away from violence.(6)

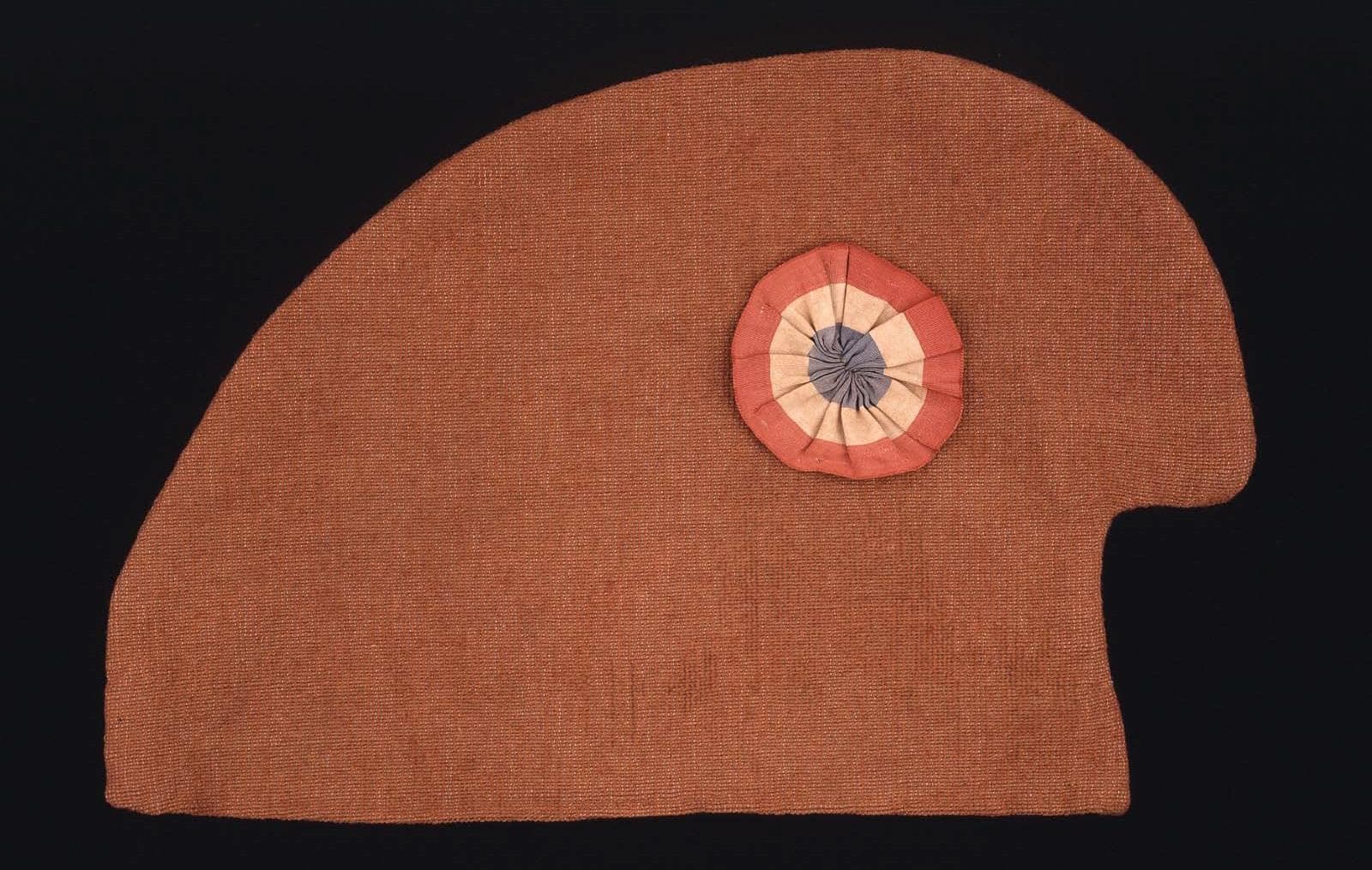

A pen-and-ink drawing in the Crocker’s permanent collection, Portrait of a Young Boy in Revolutionary Costume by Philippe-Auguste Hennequin [fig. 4], captures the visage of one child, whose countenance and revolutionary-coded attire reflect the role of children in the turmoil of the 1790s. Hennequin—an artist whose 1821 drawing Annunciation [fig. 5] is also featured in Reform to Restoration—drew this boy in October 1796, while imprisoned in the same cell that had held Queen Marie-Antoinette three years prior. The boy, possibly the child of the jailer, wears the type of soft felt conical cap that came to be associated with the French Revolution [fig. 6], a reference to an ancient Roman tradition.(7) Whether intended as a preparatory study or a distraction during his confinement, the drawing reveals Hennequin’s careful study of the boy’s features and costume. The profile composition set in an oval alludes to the format of portrait medals, imbuing the sitter with a nobility and gravitas beyond his years. Moreover, Hennequin captures the boy’s self-assured posture through crossed arms and a direct gaze beyond the frame. Despite these trappings of authority, the boy’s slight stature and youthful features are a reminder of his innocence. Whether the boy is a revolutionary or simply dressing up as one is ambiguous.

Both the idealized family in Debucourt’s Paternal Pleasures and Hennequin’s young revolutionary reveal the power of children to embody nationalistic ideologies. In response to the social and political turbulence of the late 18th century, French artists sought to communicate not only the immediate crisis— which greatly affected children—but also a vision of a hopeful future, where thriving families represented the ultimate civic virtue. As seen in both the Crocker’s drawing collection and the works in Reform to Restoration, children were not merely passive witnesses to the upheavals of Republican France, but potent symbols of the nation’s aspirations and anxieties.

By Sarah Farkas

Associate Curator of Art

1. Isabelle Mayer-Michalon, Reform to Restoration: French Drawings from Louis XVI to Louis-Philippe (1770–1830), ed. Alvin L. Clark (The Horvitz Collection, 2024), 262.

2. Mayer-Michalon, Reform to Restoration, 262.

3. Mayer-Michalon, Reform to Restoration, 262.

4. Mayer-Michalon, Reform to Restoration, 262.

5. Ivan Jablonka, “Children and the State,” The French Republic: History, Values, Debates, ed. Edward Berenson et al. (Cornell University Press, 2011), 396.

6. Julia M. Gossard, “Child Gangs and Motherly Duty at the Onset of Revolution,” Age of Revolutions, August 7, 2017, https://ageofrevolutions.com/2017/08/07/child-gangs-and-motherly-duty-at-the-onset-of-revolution/.

7. The Greek historian of Rome Appianòs or Appian of Alexandria (circa 95–165 CE) references these caps in his writings. They were given to newly freed enslaved people or captives as a symbol of their freedom. See Appian, The Civil Wars 2.119.